on monuments

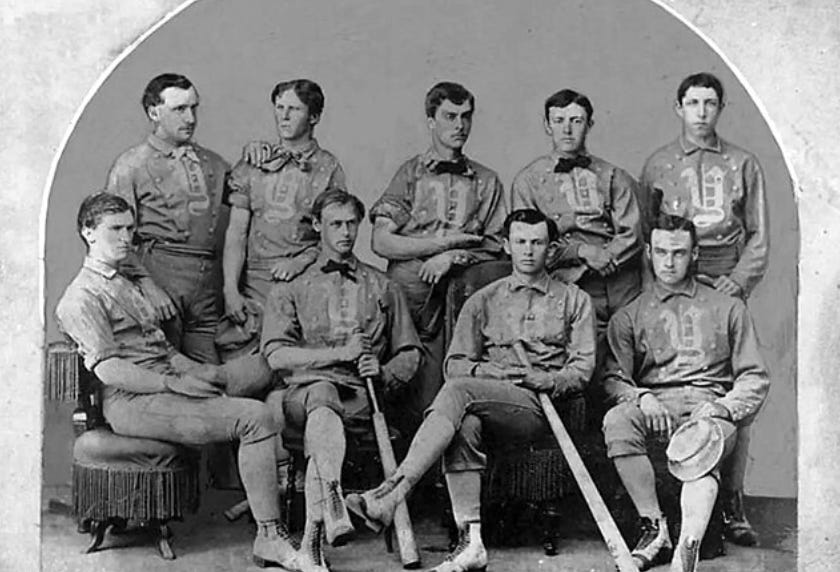

Baseball and its icons

Before we talk about baseball, we must talk about America. About its mother. About a land that grew and nurtured and raised its people until it couldn’t anymore, crumbling under the weight of its own perceived successes. There is nothing to be said about America that hasn’t been said, yes, but the world of sports is so rich and so tantalizing that it would be a crime to not visit it again.

America did not invent baseball. It began in France, then in England before making its way to Canada and ultimately settling down in America. But it wanted to. In 1839, 16-year old Abner Doubleday was resting in his hometown of Cooperstown, New York when the idea struck him. Four bases, seven batters, and a six-foot ring in which pitchers would “toss” to them. Mining engineer Abner Graves was the only one to have seen it:

“Just in my present mood I would rather have Uncle Sam declare war on England and clean her up rather than have one of her citizens beat us out of Base Ball.”

And thus, it was not a sport, but an ideal. An ideal that a country needed so desperately that it created its own origin story, built its own mythology on top of borrowed bones. Cooperstown is irrelevant if not for our need for ownership, our need for history and myth to blur into something more than truth. Reshaping the echo until it responds in their voice.

Yet, baseball has always been a game of failure. The best hitters in the world only get on base three out of ten times. Your team is lucky if you make the World Series once in a ten-year span, and it must be divine intervention if by God’s grace you win. It is a game of who can keep the other team the smallest. Not who can score the most points or be the most physical or garner the most support, but who can make the other look dismissable. Make them look forgettable.

Why we become vocal in wishing harm to another only in times of political strife, personal attacks, or sporting events is only puzzling if you haven’t done it yourself. They (we) all share one thing in common: the desire to see something greater than ourselves fail. The athlete and the bully and the politician are so disconnected from the common man that it simply does not matter if one wishes hardships upon them.

In 1969, Mets pitcher Tom Seaver spoke out against the war in Vietnam: “If the Mets can win the World Series, then we can get out of Vietnam.” And Shea Stadium – his home, his place of work, his comfort – despised him for it. They almost booed him off the field. For reminding them that their sons were dying in jungles half a world away. For making baseball feel smaller than the bodies being shipped home. For stripping their ideals down to words and flipping it on its head.

There is no amount of practice that can overcome the mathematics of scarcity. That can overcome the cruel economics of a system that needs most dreams to fail so that a few might seem worth chasing. No, it is not a Sisyphean task, but it is unrealistic to pretend that the boulder isn’t unbearably heavy.

A hero becomes a memory becomes a mistake becomes a moment we try to forget. The crowd’s roar turns to silence turns to boos turns to something that sounds like grief but tastes like fear. In the time it takes for a fastball to reach home plate, Seaver went from saving games to questioning wars, the distance between those two things greater than any pitch he’d ever thrown. The stadium lights still shone on the same field, but suddenly they were illuminating all the wrong truths. All the letters home that ended mid-sentence. All the ways we use games to give shape to a world that’s losing its shape entirely.

We have already spoken for too long. The game is almost over.